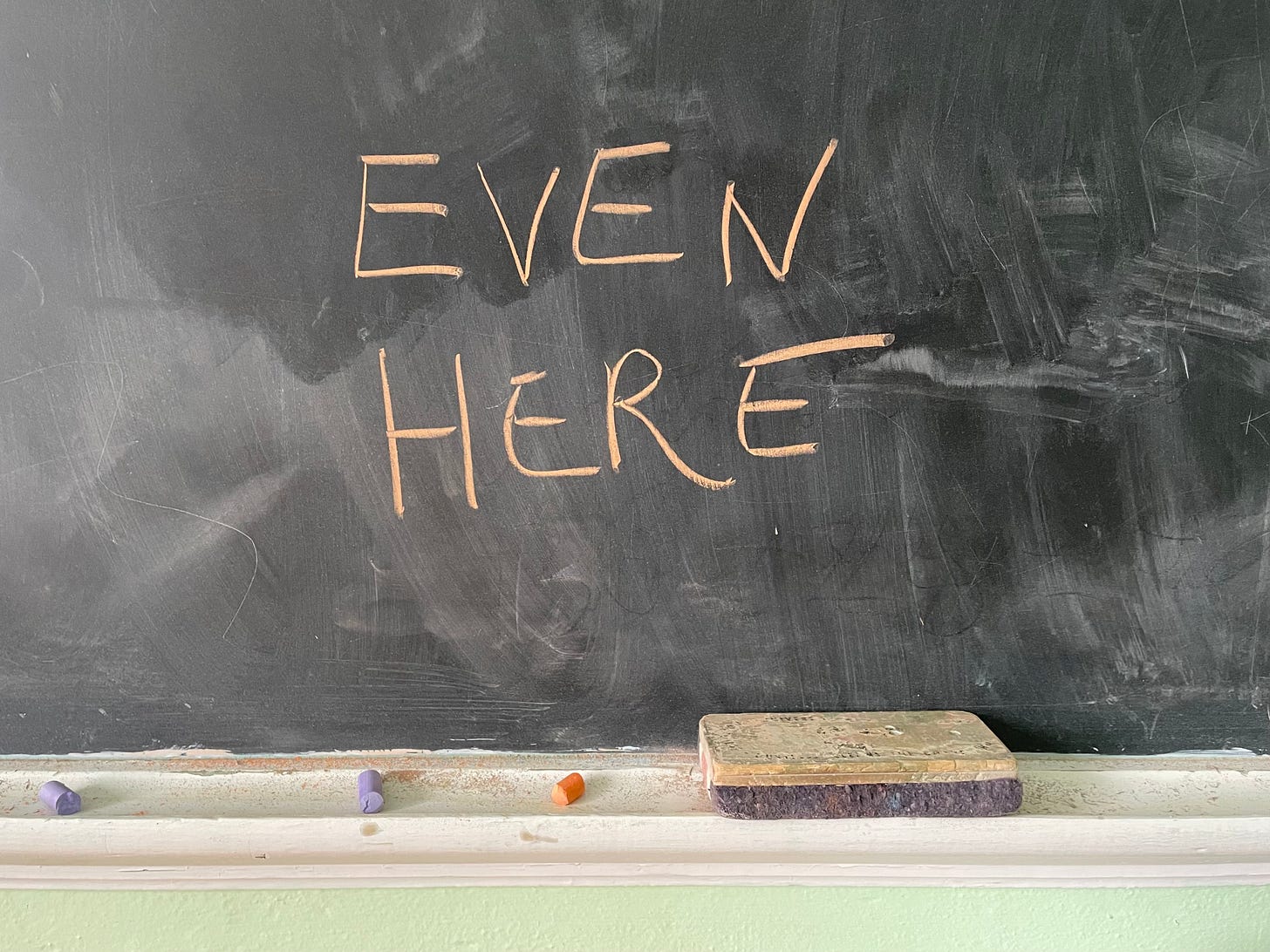

Making Art, Even Here

On creativity as a good sister

Hello friend,

I shouldn’t be writing here right now.

By all accounts, I should be allocating 100% of my time and mental resources to a document titled “THESIS.docx”. The word count is currently half of what I hope my future (non-academic) book will be.

As my preschooler would say, it’s mega big.

This spring, in fact, I laid down the law and decreed that I would not be allowed to write for fun until I had turned in my dissertation: a degree decree, if you will. I had just been consumed by writing a massive creative essay, and I was worried that my art was turning into a form of procrastination. My brain was all too eager to focus on telling stories about Italian art museums rather than processing my fears about finishing my PhD. Pleasure would need to wait until it had been earned; it was time to dedicate all my mental cylinders to The Task.

Summer came, and I started to wither.

I was alone in a windowless room with nothing but The Task and my fear.

Things got very, very bad.

On a phone call with a friend in that very, very bad place, she asked if there was any way to imagine turning my dissertation into an art project. The only thing I could imagine was annotating a printed version of my future dissertation with photographs, maybe some nice endpapers. But it felt abstract and dependent on… actually writing the thing.

I talked to my mom about the idea of treating my thesis as art, and she got really quiet, like she does right before she’s going to say something important.

“Marina,” she said, “you must write this thing as only you can.” She told me to approach my PhD as I approach my art, to bring my whole self—weird and wonderful—into the process. My voice had a place here.

And I wondered,

What would it look like for ME to write a dissertation?

This turned the very, very bad place into a creative constraint.

Before my moratorium on creativity, I was in New York City for a writing workshop, which happened to overlap with Uncommon Denominator, a solo show by one of my favorite artists at the Morgan Library. I had first discovered Nina Katchadourian’s art at SFMOMA: two video screens showed the artist lip-syncing a duet with herself to “Under Pressure” in an airplane bathroom. This was part of her ongoing art project, Seat Assignment (2010-present), where on long-haul flights she improvises with art-making using only a camera phone and the materials she finds around her. It is a practice of radical presence, through a "complete investment in the present moment, the materials at hand, and faith and attentiveness to both".

In Uncommon Denominator, Katchadourian had carte blanche to create an exhibition of her artworks, artifacts from her family’s history, and objects from the Morgan Library’s archives. The result was cheeky and profound, weird and wonderful. I gravitated over to the wall showing photographs from Seat Assignment, including an image of a lakeside garden overlaid with (giant) peas. Katchadourian had written the text panel:

The project puts to the test many of the premises that guide my artistic practice: Is there always more than meets the eye? Can a cramped, transient space, like an airplane seat, be my studio? Can I make something out of nothing, working under conditions where art doesn’t seem likely or possible?

Those words resonated somewhere deep, though in that moment, in a museum in Manhattan about to start a writing workshop, the question felt comfortably hypothetical.

But a few weeks later, when my mom told me to make art at the dissertation desk, I thought back to these words. Art seemed impossible, but here was an artist who modeled an approach to possibility through interesting questions:

“Can I make art where it doesn’t seem likely or possible?”

Can I make art, even here?

My art-making started accidentally at a picnic table in a lavender farm. The fields had WiFi, a table shielded from the hot summer sun by a hut, and views of rolling hills. I opened my laptop and took a deep breath.

My fingers hovered over my laptop, on the verge of touching The Task, and suddenly I was overcome by an urge to pay attention to what the experience of facing my work felt like. I rubbed my hands over the painted wood of the picnic table, the bumpy keys of the keyboard, my cheeks and eyebrows. Then I ducked below the picnic table and grabbed a small rock from the gravel underneath. The rock was smaller than the palm of my hand, rough, angular. I placed it next to my computer as I typed, I danced it with my fingers as I thought. It became a friend, a witness, an anchor.

I took the rock home with me, and put it on my desk.

The next morning, I visited Lake Memphremagog as I waited for the lavender farm to open. Alarm bells were ringing in my head as my rendezvous with The Task approached, and I tried to find some quiet by dipping my toes in the cold water.

My feet navigated carefully over poky pebbles and shell edges, until I found a soft place to stand, with a smooth rock massaging the ball of my right foot. The surface of the lake reflected the puffy clouds above, minnows came brazenly close to my toes. Before turning back to my car, to the picnic table, to The Task, I bent over to pick up the friendly rock from the water. It had heft to it. Later that morning, as I balanced my fear and my capacity to reach out and touch The Task, the weight of the rock kept me steady.

I brought the rock home with me that evening. Then another, then another. Every day I touched The Task, I chose a rock that embodied how I felt, that protected me, that made me laugh. Each rock became a manifestation of the intangible textures of my efforts.

Soon, I had jars overflowing with this strange and surprising

art.

Creativity, to paraphrase Audre Lorde, is not a luxury.

School drilled the opposite lesson into me as a Depressed adolescent: if I was not well enough to go to class, then I should not be allowed to make art. If I was unable to suck it up to do my math homework, then it would be indulgent and wrong for me to go to theatre rehearsal.

But if we are to face the things that scare us, to enact “the changes which we hope to bring about through [our] lives” (Audre Lorde), we must be in right relation with our innate capacity. Sustainable movement comes from listening to the parts of us that are strong, not pushing pushing pushing fear into submission.

Creativity is a good sister.

She is strong, she has ears for the voice of intuition, she knows how to have a good time.

She invites us to lean what is heavy against her warm shoulder.

She stares down despair and fear and frustration and boredom and says,

“Betcha we can make something weird and wonderful,

even here.”

It’s winter now. The rocks of Québec are hibernating under heavy mounds of snow. The newest iteration of my dissertation desk is in a tiny room with a chalkboard and creaky radiator. The fear still sits vigil with me every time I open my laptop to touch The Task.

One afternoon, I looked up at the chalkboard where I had broken down The Task into a list of reasonable chunks, prime for crossing off. Fear froze me like a statue. Movement felt impossible.

But a poem felt possible. I scribbled down words to paint the panic, the frustration, the paralysis, using imagery that bubbled up from my belly.

And then something very mysterious happened.

As I wrote, my brain started to thaw, then my arms and my fingers warmed up enough to type tentatively in my dissertation. I went back and forth between “THESIS.docx” and “SisterText.docx”, braiding together the intellectual and poetic, leaning on my creative capacity like a sister.

This kept happening. I’d sit at the dissertation desk and meet fear with a poem. Then another, then another. The poetry teaches the dissertation fluidity; the dissertation teaches the poetry rigor. Together, we are sustaining motion.

I like to imagine how I will feel on the day I defend my dissertation. I picture my blue shoes and moon brooch, the smiles of the friends I will invite as witnesses, the shock in my chest as I step into the other side of done.

And I am also making plans for what I will do with these jars of rocks and the folder full of sister texts: this tangible evidence that the impossible can shift into the possible, that creativity can thrive in the margins like sidewalk-crack-grass, that making art can reconnect us with our deepest aliveness.

I know these things to be true, because I have touched them.

Tidbits

✨ My essay “Sister”, an experimental piece about belonging and the sacred feminine, was published in Khôra. (Sisterhood seems to be a theme I keep coming back to.)

🪨 Check out the videos of my PhD rocks on Instagram: fraud, magic, tangible, perspectives, presence, evidence of care, unstuck, being held, impossible, régénération.

🚽 Read more about Nina Katchadourian’s “Seat Assignment” project in last year’s “Art for the Wilderness” series: meeting restraints with playfulness. (And if you’re feeling adventurous, why not make your own “Lavatory Self-Portraits in the Flemish Style” next time you’re on an airplane - it’s fun.)

👀 I facilitated an in-person workshop, “Looking at Life like Art”, at University of Pennsylvania’s Collegium Institute this November.

If you work in a museum and might be interested in hosting a workshop, please reach out! I’m plotting up ways to adapt this program to a museum context.

📚 A lot of beautiful new books are coming out in the next few months! Pre-ordering is one of the best ways to support authors. Here are some books I am particularly excited about: Black Liturgies by Cole Arthur Riley, Practices for Embodied Living by Hillary McBride, The Mother Artist by Catherine Ricketts, Beyond Ethnic Loneliness by Prasanta Verma, and Slow Looking at Art by Claire Bown.

Wishing softness and solidarity to us all. Let’s find new ways to make art where it doesn’t seem likely or possible, together.

Warmly,

So good, and such a good perspective on dealing with the hard things in life. On a practical note, I loved the read along. It was a joy to listen to while working.

This is so gorgeous! And offered me new avenues into some of my own thoughts and activities - what a hospitable space you've made.